The Reorder Buffer (ROB) and the Dispatch Stage¶

The Reorder Buffer (ROB) tracks the state of all inflight instructions in the pipeline. The role of the ROB is to provide the illusion to the programmer that his program executes in-order. After instructions are decoded and renamed, they are then dispatched to the ROB and the Issue Queue and marked as busy. As instructions finish execution, they inform the ROB and are marked not busy. Once the “head” of the ROB is no longer busy, the instruction is committed, and it’s architectural state now visible. If an exception occurs and the excepting instruction is at the head of the ROB, the pipeline is flushed and no architectural changes that occurred after the excepting instruction are made visible. The ROB then redirects the PC to the appropriate exception handler.

The ROB Organization¶

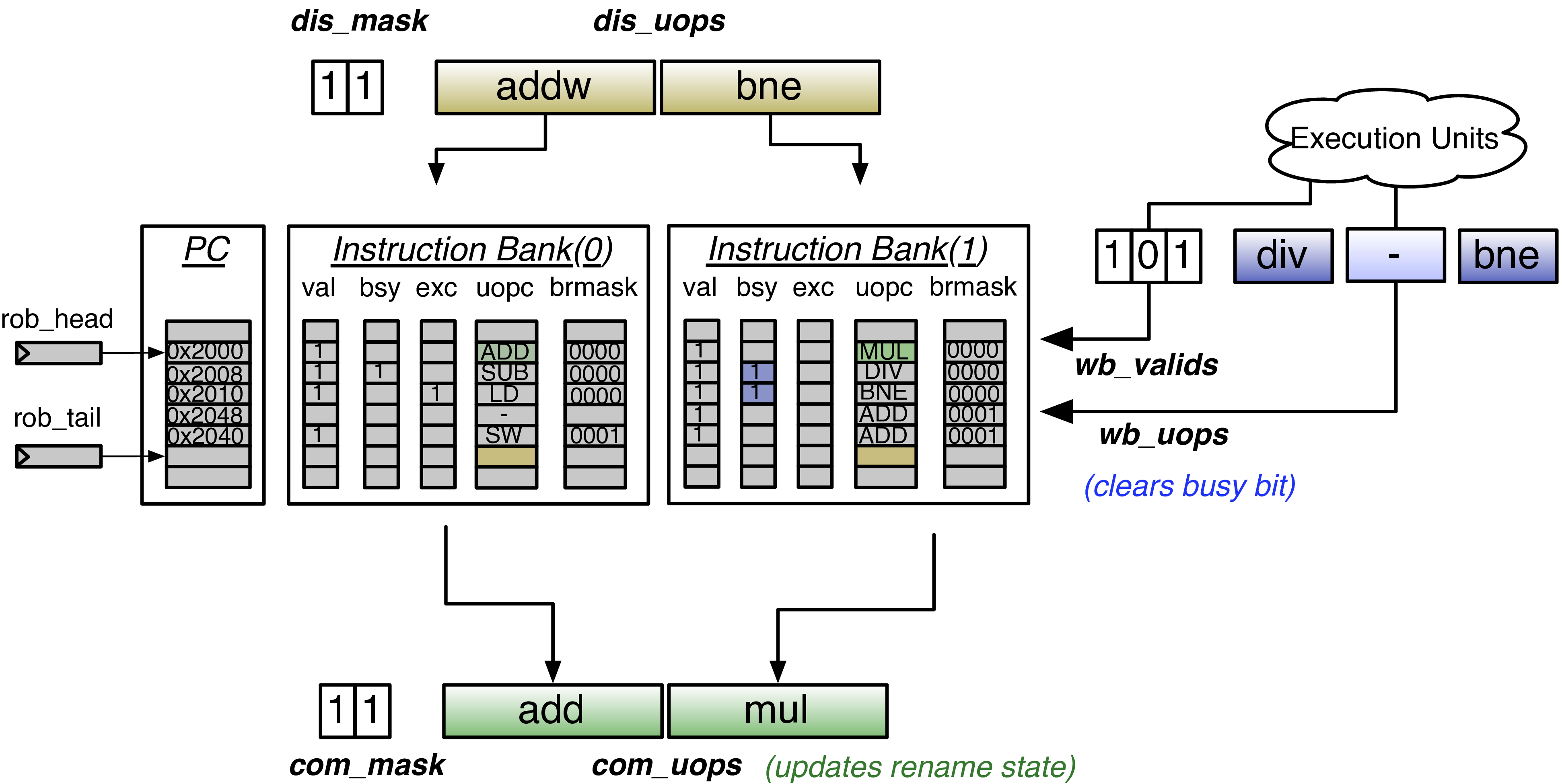

Fig. 16 The Reorder Buffer for a two-wide BOOM with three-issue. Dispatched uops (dis uops) are written at the bottom of the ROB (rob tail), while committed uops (com uops) are committed from the top, at rob head, and update the rename state. Uops that finish executing (wb uops) clear their busy bit. Note: the dispatched uops are written into the same ROB row together, and are located consecutively in memory allowing a single PC to represent the entire row.

The ROB is, conceptually, a circular buffer that tracks all inflight instructions in-order. The oldest instruction is pointed to by the commit head, and the newest instruction will be added at the rob tail.

To facilitate superscalar dispatch and commit, the ROB is

implemented as a circular buffer with W banks (where W

is the dispatch and commit width of the machine [1]). This

organization is shown in Fig. 16.

At dispatch, up to W instructions are written from the Fetch Packet

into an ROB row, where each instruction is written to a

different bank across the row. As the instructions within a Fetch Packet

are all consecutive (and aligned) in memory, this allows a

single PC to be associated with the entire Fetch Packet (and the

instruction’s position within the Fetch Packet provides the low-order

bits to its own PC). While this means that branching code will leave

bubbles in the ROB, it makes adding more instructions to the ROB very

cheap as the expensive costs are amortized across each ROB row.

ROB State¶

Each ROB entry contains relatively little state:

- is entry valid?

- is entry busy?

- is entry an exception?

- branch mask (which branches is this entry still speculated under?

- rename state (what is the logical destination and the stale physical destination?)

- floating-point status updates

- other miscellaneous data (e.g., helpful for statistic tracking)

The PC and the branch prediction information is stored on a per-row basis (see PC Storage). The Exception State only tracks the oldest known excepting instruction (see Exception State).

Exception State¶

The ROB tracks the oldest excepting instruction. If this instruction reaches the head of the ROB, then an exception is thrown.

Each ROB entry is marked with a single-bit to signify whether or not the instruction has encountered exceptional behavior, but the additional exception state (e.g., the bad virtual address and the exception cause) is only tracked for the oldest known excepting instruction. This saves considerable state by not storing this on a per entry basis.

PC Storage¶

The ROB must know the PC of every inflight instruction. This information is used in the following situations:

- Any instruction could cause an exception, in which the “exception pc” (epc) must be known.

- Branch and jump instructions need to know their own PC for for target calculation.

- Jump-register instructions must know both their own PC and the PC of the following instruction in the program to verify if the Front-end predicted the correct JR target.

This information is incredibly expensive to store. Instead of passing PCs down the pipeline, branch and jump instructions access the ROB’s “PC File” during the Register-read stage for use in the Branch Unit. Two optimizations are used:

- only a single PC is stored per ROB row.

- the PC File is stored in two banks, allowing a single read-port to read two consecutive entries simultaneously (for use with JR instructions).

The Commit Stage¶

When the instruction at the commit head is no longer busy (and it is not excepting), it may be committed, i.e., its changes to the architectural state of the machine are made visible. For superscalar commit, the entire ROB row is analyzed for not busy instructions (and thus, up to the entire ROB row may be committed in a single cycle). The ROB will greedily commit as many instructions as it can per row to release resource as soon as possible. However, the ROB does not (currently) look across multiple rows to find commit-able instructions.

Only once a store has been committed may it be sent to memory. For superscalar committing of stores, the Load/Store Unit (LSU) is told “how many stores” may be marked as committed. The LSU will then drain the committed stores to memory as it sees fit.

When an instruction (that writes to a register) commits, it then frees the stale physical destination register. The stale pdst is then free to be re-allocated to a new instruction.

Exceptions and Flushes¶

Exceptions are handled when the instruction at the commit head is excepting. The pipeline is then flushed and the ROB emptied. The Rename Map Tables must be reset to represent the true, non-speculative committed state. The Front-end is then directed to the appropriate PC. If it is an architectural exception, the excepting instruction’s PC (referred to as the exception vector) is sent to the Control/Status Register (CSR) file. If it is a micro-architectural exception (e.g., a load/store ordering misspeculation) the failing instruction is refetched and execution can begin anew.

Parameterization - Rollback versus Single-cycle Reset¶

The behavior of resetting the Rename Map Tables is parameterizable. The first option is to rollback the ROB one row per cycle to unwind the rename state (this is the behavior of the MIPS R10k). For each instruction, the stale physical destination register is written back into the Map Table for its logical destination specifier.

A faster single-cycle reset is available. This is accomplished by using another rename snapshot that tracks the committed state of the rename tables. This Committed Map Table is updated as instructions commit. [2]

Causes¶

The RV64G ISA provides relatively few exception sources:

- Load/Store Unit

- page faults

- Branch Unit

- misaligned fetches

- Decode Stage

- all other exceptions and interrupts can be handled before the instruction is dispatched to the ROB

Note that memory ordering speculation errors also originate from the Load/Store Unit, and are treated as exceptions in the BOOM pipeline (actually they only cause a pipeline “retry”).

Point of No Return (PNR)¶

The point-of-no-return head runs ahead of the ROB commit head, marking the next instruction which might be misspeculated or generate an exception. These include unresolved branches and untranslated memory operations. Thus, the instructions ahead of the commit head and behind the PNR head are guaranteed to be non-speculative, even if they have not yet written back.

Currently the PNR is only used for RoCC instructions. RoCC co-processors typically expect their instructions in-order, and do not tolerate misspeculation. Thus we can only issue a instruction to our co-processor when it has past the PNR head, and thus is no longer speculative.

| [1] | This design sets up the dispatch and commit widths of BOOM to be the same. However, that is not necessarily a fundamental constraint, and it would be possible to orthogonalize the dispatch and commit widths, just with more added control complexity. |

| [2] | The tradeoff here is between longer latencies on exceptions versus an increase in area and wiring. |